When Condemning Antisemitism Is Safe — and Naming Its Drivers Is Not

Author’s Note: This essay has been expanded to address how rhetorical failures around antisemitism span political lines. This updated version reflects where my thinking ultimately landed.

In the days following the antisemitic attack in Bondi — where Jews gathered during Hanukkah were targeted in a brutal act of violence — public statements arrived swiftly. They were solemn, polished, and carefully worded. Political leaders, public figures, and institutions condemned antisemitism, expressed grief, and affirmed shared humanity. Many of these statements were sincere. All were familiar.

For much of the broader public, these statements served their intended purpose: they reassured, they comforted, they signaled moral decency. For Jews, however, they landed differently. Not because we doubted the goodwill behind them, but because we have learned — through history and experience — to listen for more than tone. We listen for whether the speaker understands the path that led to violence, not only the violence itself.

What struck many Jews was not the absence of condemnation, but its uniformity.

For Jews listening in this moment, the question was never whether antisemitism would be denounced. It was whether those speaking understood how we arrived here — and whether they were willing to say so out loud. We listened not only for compassion, but for comprehension. Not just for sympathy, but for moral diagnosis.

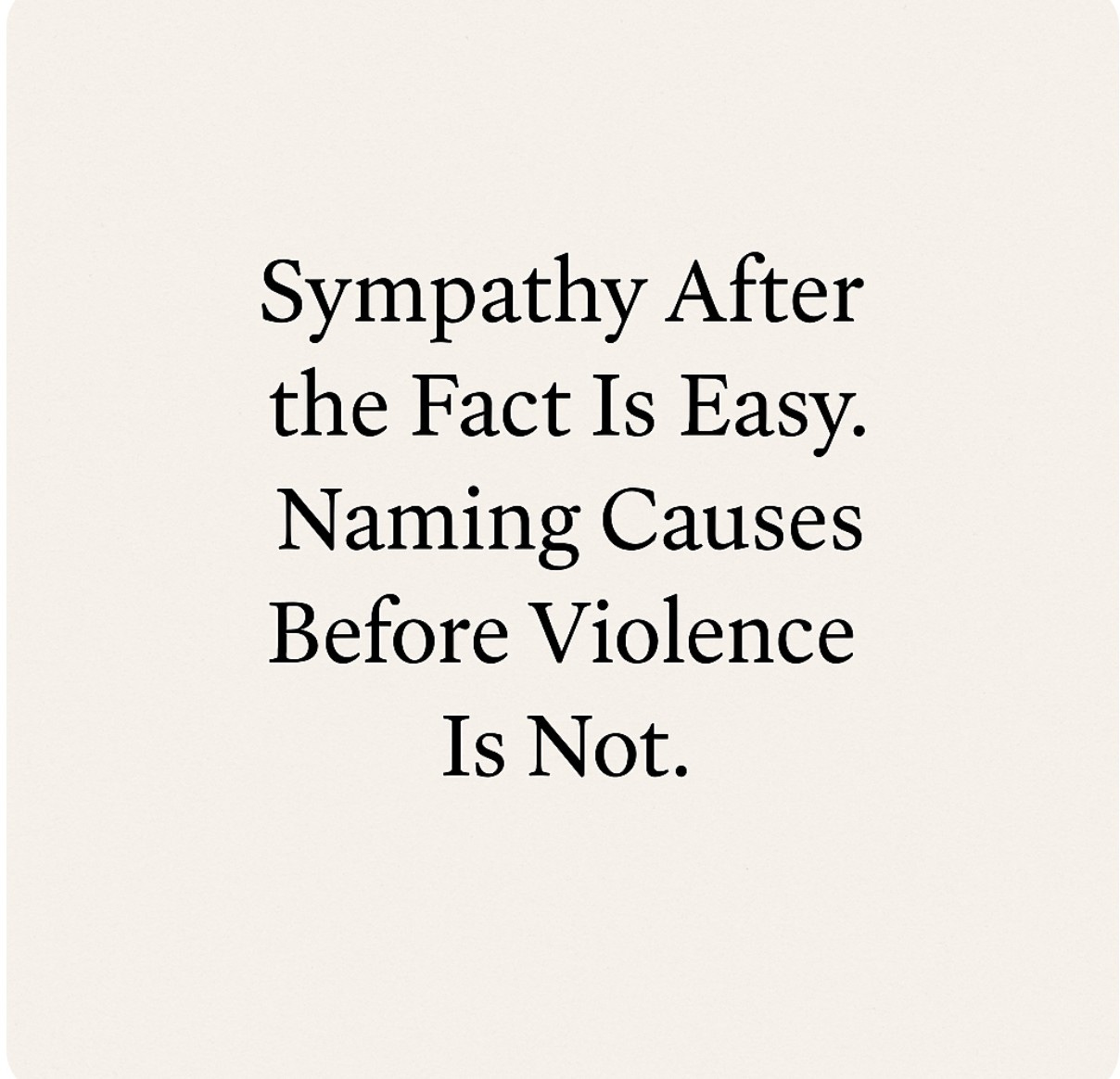

That distinction matters. Because condemning antisemitism has become politically safe. Naming what is driving it has not.

In an era of heightened polarization, leaders have learned that expressions of empathy carry little political cost, while specificity carries risk. Condemnation has become ritualized — expected, almost automatic. Diagnosis, by contrast, requires judgment. It requires identifying ideas, movements, or narratives that may enjoy popular support in certain quarters. And it is precisely that step that is now routinely avoided.

In response to the Bondi attack, New York Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani described the violence as “a vile act of antisemitic terror,” expressing solidarity with Jewish communities confronting a global surge in antisemitism. The language was clear and appropriate. It named antisemitism directly. It acknowledged Jewish vulnerability. That matters — and it deserves to be acknowledged.

But this clarity arrived only after the unthinkable had already happened.

In earlier discussions about rhetoric closely associated with violence against Jews — including phrases with a long and bloody history — Mamdani emphasized nuance over repudiation. Words, he argued, mean different things to different people, and it was not the role of political leaders to police language. The framing was calm, intellectual, and principled. It also exemplified a pattern Jews have come to recognize all too well.

For Jews, language has never been neutral. Slogans do not emerge in a vacuum; they travel. They accumulate meaning through repetition, context, and history. Long before violence erupts, language does its preparatory work — narrowing moral boundaries, signaling who may be targeted, and who will be defended afterward.

Jews know this because we have lived it repeatedly. From medieval accusations to modern propaganda, from whispers to chants, from words to wounds, the pattern is painfully consistent. Language softens the ground. It normalizes hostility. It prepares the moral imagination for acts that would otherwise be unthinkable. To treat incendiary rhetoric as endlessly ambiguous is not an act of balance; it is a refusal to reckon with how hatred actually spreads.

The contrast is telling. Violence is condemned once it erupts. But the rhetoric that helps normalize hostility toward Jews before it turns lethal is often treated as too complex, too subjective, or too politically fraught to confront directly.

This gap — between moral clarity after the fact and hesitation before it — sits at the heart of the current crisis.

The same pattern appears in statements from some of the most respected voices in American public life. Following the Bondi attack, former President Barack Obama issued a message of sympathy, writing that he and Michelle were praying for the families mourning loved ones after a “horrific terrorist attack against Jewish people,” and invoking the light of the menorah as a symbol of comfort amid darkness.

It was a humane and dignified response. It named the victims. It named antisemitic terror. It offered solace rather than abstraction.

And yet, Obama’s language also reflects a broader model of moral leadership that has come to dominate public discourse: careful, restrained, emotionally resonant — and deliberately non-diagnostic. The attack is mourned. Antisemitism is condemned. But the ideas, movements, and narratives that increasingly frame Jews as legitimate targets remain unnamed.

This is not a failure of compassion. It is a failure of attribution.

For more than a decade, American political culture — particularly within elite institutions — has equated moral seriousness with caution. Leaders have been trained to speak in ways that avoid offense, preserve coalitions, and maintain rhetorical balance. Over time, that caution has hardened into habit. Empathy has become the endpoint rather than the beginning of analysis. The result is a public language that soothes but does not clarify, that reassures but does not warn.

President Donald Trump also responded to the Bondi attack by calling it “a purely antisemitic attack.” His language was blunt rather than lyrical, but the structure was the same: condemnation without diagnosis. Antisemitism was named; its contemporary fuel was not. Different style, same endpoint.

This is not a partisan observation. It is a rhetorical one.

What makes this rhetorical pattern especially dangerous is not that it denies antisemitism exists, but that it renders it contextless. By stripping antisemitic violence of its ideological scaffolding, leaders transform it into an isolated pathology — a sudden eruption of hate rather than the predictable outcome of narratives allowed to circulate unchecked. This framing reassures the public that the problem is anomalous, while signaling to those steeped in the rhetoric that their worldview remains largely undisturbed. Silence, in this sense, does not merely fail to prevent harm; it functions as permission. It allows antisemitism to present itself as moral critique, as political grievance, or as righteous anger — anything but what it is. For Jews, who have watched this pattern repeat across centuries and continents, the refusal to name causes does not feel like restraint. It feels like recognition without responsibility. And recognition without responsibility is not moral leadership; it is abdication.

Across ideological and political lines, leaders now reliably denounce antisemitism while stopping short of naming the forces that animate it in our time. Whether the language is elevated or plainspoken, empathetic or forceful, the pattern holds: sympathy is offered, but causality is avoided.

For Jews, this avoidance is not abstract. We experience antisemitism as escalation — as permission structures that form when certain narratives go unchallenged. We see slogans migrate from campus chants to street violence. We watch Jewish institutions fortify themselves while being told that naming the ideological roots of this hostility would be “divisive.”

The cost of this rhetorical restraint is not theoretical. It is measured in rising assaults, in schools requiring security guards, in synagogues hardening their entrances, and in parents quietly debating whether it is safe to display Jewish symbols in public. When leaders refuse to name what is driving antisemitism, they unintentionally legitimize the ambiguity that allows it to flourish.

Condemnations that avoid naming ideological drivers — particularly when antisemitism is entwined with absolutist anti-Zionism that casts Jews as uniquely illegitimate — may feel responsible to those issuing them. But to Jews living with the consequences, they feel dangerously incomplete.

Language shapes moral boundaries. When leaders refuse to draw those boundaries clearly, they do not remain neutral. They create space — space for radicalization, for distortion, and for the normalization of hatred disguised as critique.

This is why so many Jews hear these statements differently than their authors intend. We are not asking for performative outrage. We are asking for honesty — about where contemporary antisemitism is coming from, how it spreads, and why it has been allowed to masquerade as moral critique rather than hatred.

Condemning antisemitism is no longer the hard part. Naming its sources is.

And in a moment when Jews are being attacked in synagogues, museums, schools, and public spaces across the globe, moral clarity delayed is not neutrality. It is negligence.

For a people whose history has taught us exactly where euphemism, evasion, and moral half-measures lead, clarity is not a rhetorical preference — it is a survival imperative.

Grace Bennett is a writer, editor, and publisher. She is the daughter and granddaughter of Holocaust survivors and is currently at work on Fischel the Baker, a three-generation family memoir.

Mamdani and Obama are two sides of the same coin. Would NEVER call them different. Obama is simply more subtle about his biases and prejudices.

This essay will change how I communicate about Jihadism. No more being on the defensive. If I’m not mistaken, your position fits well with ISGAP’s recent report on the Muslim Brotherhood’s tactics for gaining traction in the U.S. If you’re on FB, I’ll follow you. Thank you so much for this piece. Joe Gorton